The full report about Mission 4636 is “Crowdsourcing and the crisis-affected community”, published by the Journal of Information Retrieval. It is the only comprehensive report on the crowdsourced response to Haiti that has passed blind peer review, and the only to focus on the role of the Haitian population, both in and outside of Haiti. It is considered the canonical account, now taught in Disaster Management schools.

Update, 2013: More than two years since we wrote the article, it has gone into print! It was worth the wait: it is right that the first blind peer-reviewed journal article about humanitarian crowdsourcing, in any context, takes the perspective of the crisis-affected population. We are also grateful that the first major journal to have a special issue on crowdsourcing thought it appropriate to review and accept a paper on technology for good. The paper is:

- Munro, Robert. 2013. Crowdsourcing and the Crisis-Affected Community: lessons learned and looking forward from Mission 4636. Journal of Information Retrieval. Volume 16, Issue 2, pp 210-266

This page is to accompany this first full report about Mission 4636. It was the first time that crowdsourcing had been used for disaster response, and is still the largest deployment of its kind to date.

Just over two years ago, Haiti was hit by one of the worst natural disasters in living memory. Despite the scale of the earthquake, most of the communication infrastructure remained intact. The Haitian community came together via radio and sms to share information about the quickly changing conditions: the locations of operational clinics and hospitals, information about missing people, the status of the international relief efforts that were arriving in the country.

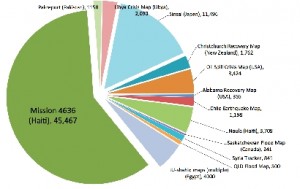

Mission 4636 processed more information than the next ten humanitarian crowdsourced deployments combined.

The majority of the people working on Mission 4636 were members of the Haitian diaspora, working from at least 49 different countries and collaborating via a simple online chat. I coordinated this initiative, which ran for several months, and for the latter half we transfered from international volunteers to paid crowdsourced workers within Haiti, creating jobs where they were needed most.

In summary, the report has the following findings:

- The greatest volume, speed and accuracy in information processing was by Haitian nationals and those working most closely with them.

- Previous reports about Mission 4636 have incorrectly credited international organizations with the majority of the work. Only 5% of messages to 4636 went through the software run by international not-for-profits, but reports like the Disaster Relief 2.0 Report inflated this 5% to appear to be the whole effort, sidelining the 95% that was Haitian run.

- No new technologies played a significant role in Mission 4636, which is again contrary to most reports to date.

- Crowdsourcing (microtasking) was an effective strategy to structure and translate information into reports that the responders among the US Military could act on.

- The online chat was vital for information sharing, as no one person could know all the possible locations and translations, but someone among the collaborating volunteers often did.

- Among social media platforms, Facebook was by far the most important.

- Translation was the largest and most important information processing task, followed by categorization and then geolocation and structuring information about missing people.

- The use of a public-facing ‘crisis map’ for the messages was opposed by the majority of people within Mission 4636 and exposed the identities of at-risk individuals.

- The majority of volunteers came together through social media and strong social ties.

- A quarter of all crowdsourced information processing was by paid workers within Haiti, who were one of the most vital workforces but have also been excluded from most other reports to date.

- The most important connections to the country were through the volunteers themselves, with direct relationships to people managing the clinics, radio stations, and individual people that we were supporting.

From the findings in the report, the following recommendations are made for organizations or individuals considering the use of crowdsourcing in response to future disasters:

- Find and manage volunteers via strong social ties.

- Maintain a ten-to-one local-to-international workforce.

- Default to private data practices.

- Publish in the language of the crisis-affected community.

- Do not elicit information for which there is not the capacity to respond.

- Do not elicit emergency response communications.

- Use social media to encourage the centralization of information.

- Establish partnerships with technology companies.

- Avoid partnerships with media organizations and citizen journalists.

- Integrate, don’t innovate or disrupt.

- Employ people with close ties to the crisis-affected region.

As I hope the report makes clear, those of us who work in technology for social good owe an overwhelming debt to the Haitians among the diaspora who put aside their personal grief to come together online and work tirelessly to help those in the greatest need. There are many non-Haitians who have also played an important role, and continue to do so. For example, Mark Belinsky helped establish some of the workflows and has continued to serve Haiti, helping to support KOFAVIV, an organization in Haiti that supports the victims of gender-based violence. Chrissy Martin helped manage a group of non-Haitians at Tufts University and has also helped Haitian telecommunication companies to establish phone banking. Ronny Hoffman was one of the most tireless volunteers, bootstrapping his knowledge of Kreyol from his work as a French teacher.

However, the greatest respect, credit and admiration should go to Haitians themselves. Many helped compile the report and it was an honor to invite them to give the final words in this article:

-

“The January 2010 earthquake woke-up the entire world, especially the people in Haiti, for a catastrophe of this proportion had not occurred in this region for more than 150 years. Those familiar with Haitian history had known that such earthquakes had plagued Haiti in prior centuries. For example, the May 7, 1842 quake that damaged the northern region of Haiti was estimated to be an 8.1 on the Richter Scale. The June 3, 1770 quake destroyed Port-au-Prince and was estimated to be a 7.5. These previous disasters, by the way, were both estimated to be of greater magnitude than the most current Jan. 12, 2010 earthquake, which registered 7.0 on the Richter Scale. This particular quake was most devastating however, for Port-au-Prince is much more heavily populated than in prior periods. While Haitians near ground zero suffered greatly, fellow Haitians in unaffected parts of the world were also traumatized for they could not assist loved ones in need.

Mission 4636 was a comforting way for me to help the Haitians people at home while I was all the way in California. We received their requests of assistance, translated them, and located the places for emergency personal to attend to. My involvement in these activities brought Haiti and my people closer to my heart, and I felt as if I was helping on the scene. Our relief effort became so large that we invited friends who were not native of Haiti, but who knew Haitian Creole to join us. Extremely touching were the enthusiasm, love, passion and dedication of every single Mission 4636 volunteer. We came together from all over the world at all hours of the day for the same, wonderful purpose – to help Haitians in crisis situation. We volunteers comforted each other in this difficult time of despair by sharing our experiences and expressing our feelings at any time we entered the chat room. The sharing was in fact a form of therapy for us. Most importantly, together we achieved an incredible feat, which in return filled us with the satisfaction and joy of helping others in need. I felt tremendously delighted that I was a part of this mission, and I hope that Mission 4636 could be a model to follow for future disasters.”

Jacqueline Oriscar, Mission 4636 Volunteer

“Like many other Haitian immigrants in the U.S., I watched with horror, despair, and helplessness the media coverage of the earthquake that devastated my home country and destroyed so many lives in Haiti. Having lived in the US for nearly two decades, I have never felt so disconnected from my home country and people than at that moment. I was not there to help or even be there, to pay witness to their suffering, in their greatest moment of need. Grief ridden, overwhelmed with guilt and sadness, I sought ways to help by providing assistance to loved ones in Haiti and making financial contributions to various aid agencies in Haiti. But, it still did not feel enough. Translating as a volunteer in Mission 4636 helped me to do something more active and emotionally engaging. It helped me to connect emotionally, though far away, with the people of Haiti. It was satisfying to know that I was making tangible contributions and that I was helping to save lives. By helping others, I also helped myself. I felt useful once again and able to participate in and sit with the pain of other fellow Haitians. It brought me closer to home and closer to my people. Indeed, it was painful at times to read traumatic stories over and over again and to read about peoples desperate cries for help and not being able to help. But, this was pain that I welcomed, a pain that made me feel Haitian.The other volunteers also provided much needed psychological support at the time. I was able to connect with others all over the world and share stories, experiences, and reactions to the earthquake. I quickly became part of a community where I was able to speak my native tongue, Haitian Creole and relate to other Haitians and friends of Haiti. Feeling isolated in a predominantly white community in Northern California, those connections were significant sources of support.”

Johanne Eliacin, Mission 4636 Volunteer

Rob Munro

June 2012